In this short blog, I want to put forward, in a relatively new way, a view of knowledge that I think challenges the idea of standardised testing, the idea that is the horror of compulsory schooling, and the idea that our most precious resource – our children – should be compelled to be propagandised wards of the so-called State. My agenda is a compilation of ideas that I believe are quite specific. In this blog the specific idea I want to get across is that knowledge is nothing more than sociocultural memory recalled situationally. The key points are that it is personal knowledge, and no-one else’s. It cannot exist outside us. It is uniquely personal knowledge, and is tinged by the sociocultural context in which one experiences life. It emerges according to the demands of the situation in which one becomes conscious of something that draws on one’s sociocultural memory, and evanesces like a clearing mist, as one becomes conscious of something else. In short, your sociocultural memory is your knowledge…the knowledge of everything you experience, whether firsthand or not. Some (and here I hazard a guess) 98% of what you think you know, is, in fact, belief rather than knowledge.

I want to re-assert the point that knowledge does not exist outside the mind. It is not found in books – sound-shapes are. It does not reside in libraries – sound-shapes do. It cannot be traded or transmitted – sound-shapes can. It cannot be objectified because it has no existence…in the sense of ‘being’ outside us. It has five quite clear and demonstrable characteristics, including that of being entirely situational. Every one of the characteristics points to a specific relationship between oneself and one’s knowledge.

The five characteristics of knowledge are that it is:

- internal,

- personal,

- unique,

- situational, and

- evanescent.

Assuming the tabula rasa arguments of such giants as Aristotle, the Stoics, the Persian philosopher Ibn Sina, the Andalusian philosopher Ibn Tufail, and John Locke, it may be argued that the accumulation of experience in one’s sociocultural environment enables one, over time, to construct both predictions and expectations of life. The accumulation of sociocultural memory is, by definition, an internal phenomenon because the evolution of one’s sociocultural memory takes place inside one’s mind.

That knowledge is personal is arguable because one’s sociocultural experience is unique. The meaning constructed by someone in a relevant sociocultural context and situation is personally constructed from personal experience. Thus, one’s sociocultural memory – which is to say, one’s knowledge – is personal.

Because no two people experience life identically, it is arguable that one’s sociocultural experiences add up uniquely to become one’s sociocultural memory – which is to say, one’s knowledge…the thing one draws on when the situation calls forth that part of the sociocultural memory relevant to a particular situation.

Thus far, I have stated that knowledge, which I claim is nothing more than one’s sociocultural memory, is internal, personal and unique. No two people construct the same sociocultural memory and therefore no two people have the same knowledge. One implication of this relates to the question of standardised testing. Nothing is standardised about one’s internal, personal and unique sociocultural memory. So, what is standardised testing actually testing?

Next, one’s sociocultural memory is stored inside one’s being. It cannot emerge all at once. It is impossible to relate one’s entire sociocultural experience in a single idea or sound-shape. Rather, like a mist that unfolds when the environmental conditions are ‘right’, one’s sociocultural memory of frogs emerges when one becomes conscious of the idea of a frog…whatever that is in one’s experience. According to the situation, the relevant part of one’s sociocultural memory emerges as one’s knowledge of frogs…or Formula One, or anything else of which one becomes conscious momentarily. Consciousness flits typically from idea to idea, from thing to thing, from moment to moment, according to how we relate to our environment from moment to moment.

Becoming conscious momentarily is key to understanding the emergent and situational nature of one’s sociocultural memory, which is to say, one’s knowledge. But one’s knowledge or sociocultural memory does not remain in one’s consciousness forever. Like the mist that unfolds when the environmental conditions are ‘right’, when the environmental conditions change…when one conscious idea is replaced by another conscious idea…one’s sociocultural memory goes back into the ‘drawer’ from which it emerged, to be held in memory until called on again. This idea is described by the use of the sound-shape ‘evanescent’.

I argue that one’s sociocultural memory, one’s knowledge, is evanescent. It emerges situationally then reverts to its pre-emergent condition (whatever and wherever that is)…that is, it evanesces…once one becomes conscious of something else. One’s sociocultural memory is not lost (although it can be because of damage or trauma, for example). It is available. We are simply no longer aware of it because our attention has moved to something else. Under-use of one’s sociocultural memory appears to lead to its fading and eventual loss (forgotten).

In sum, therefore, I have argued that we can think of knowledge as internal, personal, unique, situational and evanescent. If we add the idea that knowledge derives from firsthand experience, the about 98% (a mere guess) of what we think we know is no more than faith-based belief in the credibility of others. None of us ‘knows’ that light takes about eight minutes to travel to earth from the sun. None of us has travelled the distance and proven by firsthand experience that this is a fact. We all believe it because we choose to take on faith the credibility of a scientist who tells us it is so.

This view of knowledge, I think, challenges the idea of standardised testing. Standardised testing tests one’s ability to recall someone else’s sequence of sound-shapes. It does not always test one’s knowledge, one’s sociocultural memory, constructed from primary experience. The standard is not reflective of an individual’s sociocultural memory but rather that of the tester (by which I mean typically the so-called State, which, arguably, uses testing to stratify society and to condemn those who do not ‘fit’ the bell curve, just so, to a life of doubt and uncertainty).

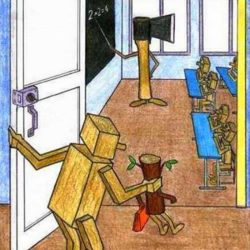

Compulsory schooling is nothing more than a so-called State’s way of standardising the population according to a dominant ideological or propagandist position that maintains the power status quo. It also identifies those who are more likely to conform to the requirements of the so-called State, and those likely to ’cause trouble’ by thinking independently intellectually, and critically…that is, differently. As one senior Church official put it in the formative years of the development of a ‘national school system’ in Australia, what was needed was an education that taught the ‘lower classes’ sufficient to enable them to obey rules and regulations but not enough to enable them to challenge the established authority. Based on an understanding of knowledge as the sum of one’s sociocultural memory, itself predicated on firsthand experience in addition to a huge faith-based portion of that memory, it follows that compulsory schooling teaches not so much how to think, as what to think. We take on faith all the history, geography, language learning, social studies, civic studies, and so on, because we do not have firsthand experience of these things. Thus, it follows that we are told what to think, albeit in sometimes creative ways. The so-called State acts to standardise what we think because, by standardising it, it is able to stratify society and preserve its power and status in a sort of divide and conquer sense.

My wife and I ‘made our children’. We chose to bring them into existence. Our children do not ‘belong’ to us. Nor do they ‘belong’ to the so-called State. What makes the so-called State think, suddenly, when my children are four years old, that it is best placed to know my children and their wants and needs better than I, or indeed better than the children do? What authorises the so-called State to choose the form of society in which my children have to live? Why can my children not decide on the society they want when they are capable of deciding? The society the so-called State thinks is best for my children is one in which they have been propagandised to believe in the authority of the so-called State, in the correctness of the so-called State, and in the boundaries set by the so-called State. In other words, compulsory school not only denies me the right to co-construct a peaceful and relevant society with my children. It also teaches my children to be laboratory rats within a cage, free to choose to run on the treadmill, or drink from the water dispenser, or sleep when it suits them, or run up and down the ladder…but always within the confines of the so-called ‘State’s’ cage. This is not freedom, and compulsory schooling does not prepare anyone for a life of freedom based on the idea of the greatest happiness for the greatest number, or the principle of doing no harm to others.

As ever, I encourage your contributions to this thinking. I welcome comments and constructive criticism of the ideas presented here.

Kindest Regards,

Peter