Knowledge, Like Meaning, Has no Existence

In the previous blog, I discussed the idea that language is a code consisting of sound-shapes, and that if the code is mutually understood, and the speaker, writer, listener, hearer or observer, as in the case of sign language-as code, share a similar sociocultural experience of life, then similar meaning may be made of a particular sequence of sound-shapes in the mind of the reader-listener-observer, on experiencing those sound-shapes. Put simply, meaning is not conveyed by sound-shapes. Rather, it is an emergent understanding of a shared experience of life, and a shared language-as-code. In a subsequent blog on learning, I deal with the idea that even though people may share a language-as-code, and even a similar sociocultural background, novelty, expressed as difference, is the engine of learning. I touch on this lightly later below, too.

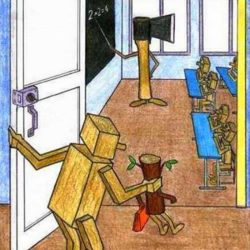

In this blog, I propose to deal with knowledge similarly. That is to say, I assert that knowledge, like meaning, has no existence[1]—at least not in the sense of its being external to those using a mutually-intelligible language-as-code. Knowledge, I argue, is not contained in books. It cannot be gained by reading. Neither is it contained in a television documentary. It cannot be ‘discovered’ by watching the documentary. Nor is it transmissible from an elder to a younger. All that is transmissible is the sound-shape, or sound-shapes, that one or other of the interlocutors believes represents something he or she knows—or, as is largely the case—believes he or she knows.

Knowledge, I claim, is a consequence of the firsthand experience of life. Everything I know that comes from other than my firsthand experience—that is, everything else—is what I believe, to a greater or lesser degree, and may be described as hearsay evidence derived from someone else’s experience. If we stop to think about this claim for a brief second, we might conclude that the majority of what I believe I know is, in fact, merely belief rather than knowledge. I concede, therefore, that when my sociocultural memory of something emerges as I become conscious of that something, that memory consists largely, indeed almost entirely, of faith-based belief.

A simple explanation will illustrate. I cannot possibly experience firsthand all the things that I now believe, about Robin Hood, about poisonous frogs in the Brazilian rainforests, about space travel, about all the creatures on the seabed, about the dangers inherent in scaling Mt Everest. I could, if I experienced such things first hand, but Robin Hood might be a bit problematic. Instead, I record my firsthand experience as memory, and thus give it form inside my mind—I in-form my experience. In-formed experience becomes an integral part of my evolving memory of life. All second- and third-hand hearsay I take with various pinches of salt, depending on the degree of my trust or faith or belief in the credibility of the source. Such hearsay, nevertheless admittedly, becomes part of what I believe to be ‘true’ about life. In this sense, the manufacturing of consent is a powerful and persuasive influence on how I construct my sociocultural memory and on the value I attribute to it. More on the manufacture of consent—by means of advertising and other forms of propaganda—in a subsequent blog.

The subtle difference between informing and in-forming now becomes apparent. Informing is understood as something that ‘exists’ in my environment and ‘flows’ here and there…an idea to which I pay little or no credence, while in-forming is something I do when I unite my internally evolving sociocultural ‘reality’ with ‘new’ experience. In-forming is internal to me. I do it. It is not done to me. No-one but I can in-form my experience. I can, of course, choose to listen to or read something—which I understand as second or third hand experience—and believe it, or not. The more I believe it, the more I am inclined to incorporate it as a credible addition to my sociocultural memory of life. Expertly manufactured consent is an insidious and not always subtle form of control that shapes my environment in ways that often lead me to choose to influence my sociocultural memory in this way. The upshot of this idea is that most of what I know is actually what I believe.

What purports to be information, therefore, is nothing more than a particular sequence of sound-shapes, typically (but not always) in a language-as-code I understand. The meaning I make of the sound-shapes, and the degree to which I believe the meaning to be a necessary part of the way I choose to construct my sociocultural memory is important. If the experience is consistent with my existing sociocultural memory then the memory is reinforced. However, if I detect difference or change, it is because such change “consists of variations, irregularities, and so on that are significant enough to impinge on the senses” (see Davis, Sumara, and Luce-Kapler below). Variation and irregularity significant enough to impinge in the senses may include the sudden appearance of a threat; becoming conscious of a cockroach on the kitchen bench on turning on the light when visiting for a late-night glass of milk, for example. It may also include subtle indications of something ‘not quite right’, almost a sixth-sense kind of intrusion into my existing sociocultural memory; such as a slight movement in the grass that suggests the presence of something…perhaps a snake, for example. Or it could be, as Davis, et al suggest, the sudden absence of something, such as when a refrigerator suddenly stops humming at night, or when the last song finishes at next-door’s party and you realise everyone’s going home. The absence of bird calls in jungle movies often suggests the presence of someone or something. The hero will suddenly say, ‘You hear that?’ The next person will say, ‘I don’t hear anything.’ The hero will say, ‘Exactly!’ just before a tiger springs from the bushes, for example.

Thus, ‘knows’ is a highly problematic idea. As already alluded to, the majority of what we think we know is merely faith-based; it is simply belief, dependent entirely on the credibility of some source other than personal firsthand experience. Knowledge is, I assert, and only ever is, situational, internal, personal, unique, and evanescent. Characterising knowledge in this way prepares the way for a journey into a new learning-teaching relationship. Let me explain.

I have already begun to address the idea of in-formation. Typically, it appears, ‘information’ (as opposed to ‘in-formation’) is thought of as something that flows in a direction, intact, and fully comprehensible in its native state. The idea of sound-shapes renders this understanding nonsensical. A conscious being needs to make sense internally of a shared language-as-code consisting of sound-shapes, whether those are the growls of lions situating each other in a pincer move to bring down some prey, or a human constructing her evolving sociocultural memory.

In fact, some scientists, particularly in the field of physics, argue that the universe is nothing but information, perhaps just a probability wave that ‘becomes’ a probability of one—‘real’—when we become conscious of it. I could argue that aspects of the universe consist as a probability of one when we become conscious of them in the context of our evolving sociocultural memory. All else in the universe, including the big bang, is, and will only ever be…as is the idea of a god…belief.

Davis, Sumara and Luce-Kapler (2000), with whom I largely agree and whom I thank for their very influential insight into in-formation and knowledge (more on their ideas below) express the idea of information as follows:

For the most part, information is uncritically discussed as though it were some invisible, massless substance that flows among people and that is lying “out there” in vast pools waiting to be absorbed through the senses…

However, the senses are not input devices, nerve fibres are not wires, neurons are not computer chips, the brain is not a central processing unit. Rather, each of these is a complex form—dynamic, adaptive, participatory.

In other words, these agents are not conduits for some mysterious fluid. Rather, it seems to make more sense to think of information in terms of events that affect the activities of these agents. In terms of the individual’s perceptions, information might be described as detectable differences or changes. That is, information consists of variations, irregularities, and so on that are significant enough to impinge on the senses…[2]

As will be developed, humans are very limited in their capacities to be consciously aware of information (what I refer to as particular and relevant sequences of sound-shapes in a shared, or similar, language-as-code), yet we seem to get by in a complex world…

Importantly, “information” refers not just to the arrival of a new sensation. It can also arrive as a sudden absence of sensation—such as the silence that is experienced when a refrigerator turns off. (The fact that absences can be as informational as presences highlights that we move through the world with sets of expectation. Interruptions of those expectations is one important form of information) (p. 5). In one sense, the sudden absence of sounds or shapes creates a sound-shape consisting of the absence. That particular sound-shape (silence) may be said to invoke different, or similar, meanings in the sociocultural memory of the different people who experience it. Movies are wonderful examples of the conditioning of a socioculture to particular sequences of sound-shape…witness the horror we share socioculturally as ‘Freddy’ works his evil on the frightened occupants of Elm Street! It’s imaginary but we have been conditioned to experience a shared sociocultural meaning and that’s what we experience together, in a sense, each of us uniquely but similarly.

The authors, Davis, Sumara, and Luce-Kapler, are frustratingly close to an ideal explanation in my opinion. However, I differ marginally from their view. I encapsulate the marginal difference in the sound-shapes ‘in-form’, ‘in-formation’, and ‘in-formed’. The importance of the three sound-shapes is that the prefix ‘in’ suggests where in-formation occurs.

I agree that both information (and in-formation) are uncritically discussed, almost taken for granted, just as are compulsory schooling, and so much more of the social context in which we live. The author’s characterisation of the dynamic, adaptive and participatory aspects of the human mind (although they write of the tangible parts of the brain and the sensory organs rather than of the mind) seems fair, and indeed useful. The dynamic, adaptive, and participatory characteristics in their description point to the internal, personal and, dare I assert at this early stage, unique nature of in-formed experience. The unique nature of in-formed experience is a consequence of our individual uniqueness. No matter how else you care to shape the argument, because two solid objects cannot occupy the same space at the same time, there is a case to be made that each of us experiences life uniquely, from a single and unique perspective, if only by seconds of degrees…

By in-formed experience, I have referred to the way we in-form the experiences we have, whether they be direct, first-person experiences, or experiences of second- or third- (and so on) hand reports of the environment in which we live. Second-hand reports of the environment in which we live approach us as sound-shapes, and we believe in them to a greater or lesser degree based on our perception of the credibility of the source, the author of the sound-shapes. We in-form the experience of encountering the sound-shapes, and of the meaning we construct of them by comparing them to our evolving and pre-existing sociocultural memory. We form neural networks that record such memory, and when triggered are able, mostly, to recall the memory as situational and evanescent knowledge.

Let me explain further. I use the example of the sound-shape ‘frog’. Immediately, I presume you are an English speaker, in your mind the sound-shape ‘frog’ invokes a sociocultural memory of what you and I think of as a frog. You have now become conscious of the sound-shape and can draw on your sociocultural memory of whatever it is you associate with the sound-shape. The experience you have had of frogs, whether first or second-hand, emerges from your sociocultural memory of frogs because your situation locates you in a relationship in which the sound-shape matters. That is to say, your knowledge is situational. It emerges only when the situation requires it to do so, and only you can know what it is you associate with the sound-shape. In this way, it may be said that, as a consequence, all the socioculturally relevant memory you have of frogs constitutes your knowledge of the amphibian, including that it is an amphibian. This knowledge emerges situationally when you become conscious of a relevant sound-shape. It need not be ‘frog’. For example, it could be a discussion of creatures that live in ponds, and keep people awake at night with their croaking, sound-shapes linked in your mind, and that you are able to relate, to your sociocultural memory of frogs, thus invoking, situationally, your knowledge of the amphibian.

Let me now turn to Formula One racing. You are now conscious of whatever it is you associate with Formula One racing, whether it is boredom, or excitement, or nothing at all, or a great deal of experience. Take a moment to reflect on the idea that as a consequence of becoming conscious of Formula One, you no longer hold in your head the sum of your sociocultural memory of frogs (although you do, now because I made you aware of the relevant sound-shape again!) What this aims to show, though, is that your knowledge of frogs is not only situational but also evanescent. Something evanescent passes away quickly. Your knowledge of frogs is relevant only while the environment brings the idea into prominence. Once the idea is no longer prominent, as it is when the subject changes to Formula One, for example, your evanescent knowledge of frogs reverts to its place in your sociocultural memory until needed again. Now you can focus on Formula One.

Leon Festinger’s (1957) theory of cognitive dissonance is relevant here. Festinger writes:

..“dissonance” and “consonance” … refer to what has been called cognition, that is, the things a person knows about himself, about his behavior, and about his surroundings. These elements, then, are “knowledges”, if I may coin the plural form of the word. Some of these elements represent knowledge about oneself: what one does, what one feels, what one wants or desires, what one is, and the like. Other elements of knowledge concern the world in which one lives: what is where, what leads to what, what things are satisfying or painful or inconsequential or important, etc (p. 9).

He also writes:

It is clear that the term “knowledge” has been used to include things to which the word does not ordinarily refer—for example, opinions. A person does not hold an opinion unless he thinks it is correct, and so, psychologically it is not different from a “knowledge.” The same is true of beliefs, values, or attitudes, which function as “knowledges” for our purposes (p. 10).

Festinger’s reference to the world in which one lives is taken by me to include both firsthand, and second- and third-hand, experience of, and belief about, “what is where, what leads to what…” and so on. Festinger is useful also because he acknowledges that opinions and beliefs are constituents of our knowledge. I have asserted above that because we experience only a small portion of all there is to experience, we necessarily take with varying grains of salt those experiences reported, using sound-shapes whose authors we trust. Such beliefs constitute part of our sociocultural memory and therefore of our knowledge, despite the fact that they are not reflective of firsthand experience. In this sense, knowledge can be understood as comprising mainly belief.

Above, I have asserted that knowledge is only ever situational, internal, personal, unique, and evanescent. I have discussed the situational aspect of knowledge in terms of an individual’s becoming conscious of sound-shapes that invoke everything relevant in the sociocultural memory of the listener, reader or observer, in a particular situation, and, importantly, according to a shared language-as-code, and sociocultural experience. The sound-shape may be simply a photo in a magazine. I have argued that knowledge is internal because it resides in the mind of the person whose sociocultural memory is recalled when a sequence of relevant sound-shapes brings that memory into consciousness momentarily. Knowledge is personal because it is in-formed by the individual to become part of the individual’s evolving sociocultural memory, and is therefore unique to the individual concerned. However, above all, the evanescent nature of knowledge that emerges situationally, on demand, from inside the individual’s sociocultural memory, as a personal record of the individual’s cumulative in-formed experience, while therefore unique to the individual, is what enables us to access our sociocultural memories on demand—because we cannot be conscious of everything all the time. As Davis, Sumara, and Luce-Kapler put it: “…humans are very limited in their capacities to be consciously aware…” (p. 5).

The important point here is that knowledge is an individual’s sociocultural memory. It cannot be bought or sold. Sound-shapes may be used to gain access to an individual’s sociocultural memory but only if the sociocultural memory is formed using the same or a similar language-as-code. 今日は熱い is a well-formed sequence of valid sound-shapes but means nothing to anyone who cannot use the Japanese language-as-code…although once one understands the English proximate sequence of sound-shapes as “it’s hot today”, one’s shared sociocultural memory of ‘hot’ can result in meaningful communication across the boundary at the margin of language-as-code. As I discussed in an earlier blog, language-as-code is meaningless. Meaning is in the mind of the reader, listener, observer, but only if the language-as-code is shared or similar. Imagine all the non-shared sociocultural memory across the various languages-as-code throughout the world…

One implication of the idea that knowledge is situational, internal, personal, unique and evanescent is that testing is at some distance from its intended outcome. The relationship between sound-shapes, language-as-code, and knowledge tested is discussed in a later blog.

As ever, please take the time to record your views using the English or Japanese sound-shape systems. They are the only two systems of which I have sufficient experience. All comments will be appreciated by my evolving sociocultural memory, and where variation and irregularity between the expectations I have of life, and those discerned among the sound-shapes used, are evident, I will consider such variation and irregularity in some detail. Thank you.

Peter Trebilco

[1] Here, I use existence in the sense of two roots; the one, being ‘ex’ (‘out of’ or ‘forth’), and the other, being ‘sistere’ (‘cause to stand’). Thus, existence here is used to convey the idea that knowledge does not stand forth independently of the mind. It rises into consciousness on demand and then evanesces until called on again.

[2] Italics in original